~

St. Nerses IV Shnorhali (1102 – 1173)

~

The Spiritual meaning of images, and the veneration of Holy icons in the Armenian Church. Illuminated Canon Tables and manuscripts.

~

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

~

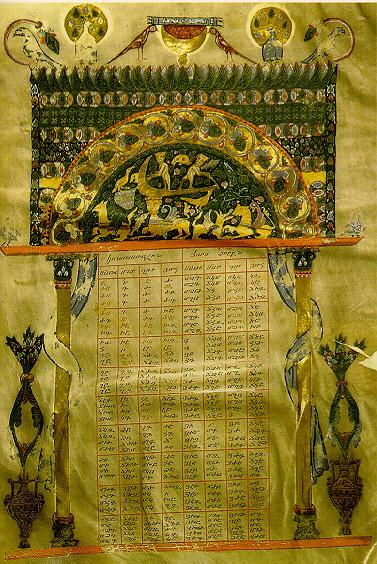

Armenian Illuminated Canon Tables, Canon I, 14th century, Gladzor monastery

~

~

The interpretation of Bible by Saint Nerses Shnorhali

~

In the Armenian theological literature there are several unique documents of art which explore and interpret the spiritual and aesthetic meaning of the Canon Tables. [1] Several such commentaries by Stepanos Syunetsi (680 -735), Nerses Shnorhali (1102-73), Grigor Tatevatsi (1344-1409) and Stepanos Dzik (17th century) are published through the years.

Of these, the commentary of Nerses Shnorhali, which forms part of his Commentary on the Gospel of St Matthew, is the most complete. [2] The frequency in which these commentaries appear, makes necessary to explore further the enthusiasm of the Armenian religious artists, throught the history, in their use of symbols, colours, motifs and decorations.

The epithet “Shnorhali” (filled with grace -“the Gracious”) by which Nerses IV Klayetsi is universally known in the history of the Armenian Church, is more than just a honorific title. In the Middle Ages, the members of various Armenian monasteries usually received various designations such as “philosopher”, ”’grammarian” or “rhetorician”. The distinctive designation “Shnorhali” (“the Gracious”) was reserved for the members of Karmir Vank (Red Monastery), an Armenian monastery at Fhoughri, where scholarly erudition and deep spiritual life depended on the interpretation of the Word of God. Nerses as well as other graduates of Karmir Vank such as Sargis Shnorhali (1100-67) were well known for their commentaries on the Gospels and the Catholic Epistles of the New Testament. [3]

For St Nerses Shnorhali the Bible holds a paradigmatic value. It traces the parameters within which all history is to be understood. This was a definition of exegesis (interpretation) found in the Discourses of St Gregory the Illuminator: “For God established this world as a school, so that creatures might learn the Creator’s care in fashioning and arranging, and might know that things visible and invisible are sustained through his providence.” What happens at present was foreshadowed in the events related in the Bible, and it makes sense to that extent. From a genuinely Christian perspective, the Bible is the only ultimately meaningful record and it imparts meaning to every other occurrence of note. In fact, this can be considered as an extension of the old doctrine of “typology”, and St Nerses follows it.

The Bible is a resource for St Nerses, even in order to justify ritual practices of the Armenian and Roman Church. The use of unleavened bread for the Eucharist is a case in point. Thus, the hospitality of Abraham can be paralleled with the Last Supper in the Upper Room. Nerses makes reference to Genesis 19:3, where the three cakes made by Abraham’s wife Sarah for the Lord were made of unleavened bread. If the Lord ate Abraham’s cake made of unleavened dough, then surely Jesus in the Upper Room also ate unleavened bread.

St Nerses develops what we might call the “doctrine of the two eyes” as a principle of exegesis. This means that two levels must be seen in scriptural texts: “Scriptures are to be understood in two ways: one is the tangible and visible, the other is the intellectual.” Scriptures have a double meaning: literal and symbolic. Presumably, in the 12th century, among Armenian writers, and especially by St Nerses, there have been made efforts of demythologization, through a hermeneutic approach to the Bible, in order to separate the cosmological and historic claims from the philosophical, ethical and theological teachings.

St Nerses Shnorhali argues that if we diverge from the literal meaning of the Bible, there will be nothing on which to hang our symbolic interpretation. For example, in the story of Adam and Eve. As St Nerses wrote, Adam and Eve and the serpent must have been real, for otherwise the race of men would not be here. Adam was a real individual and not the “universal” man. In other instances, difficulties noticed in one scriptural passage, are solved in terms of another, and a general theory of coherence seems to preside over the entire enterprise. It is obvious that St Nerses supported the generaly accepted principle of his era, that the Old Testament must be understood in terms of the Gospel. [4]

~

~

Armenian Illuminated Canon Tables, Canons IX – X, by Toros Roslin, Zeytun Gospels, 1256, Getty museum collection

~

~

The Canon Tables: Theology of Colour and Ornamentation

~

St Nerses explains how the devout Christian should approach and interpret the Canon Tables. St Nerses writes that what the Gospels teach, is that in spite of the sinful condition of the human race, the man is “in the image of God, Paradise is his abode, and the Tree of Life is the occasion of his immortality”. By referring to the the “Tree of Life” he actually means the Divine Cross. The true origins of the humans are in Paradise. It is the recollection of the original glory that leads the Christians to desire the immortal food. This immortal food is the Holy Eucharist, the Holy Communion with the holy body and the holy blood of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Paradise, in this context, embraces the beginning and the culmination of human history. That is the creation of Adam and the redemption in Christ. The first and most encompassing symbolism of the Canon Tables is therefore “paradisiacal”, the resemblance of paradise. The Garden of Paradise is walled around, not by the terrifying fire and the fiery Seraphic sword, but by the luxurious floral pictures and the colourful, splendid ornamentations of the canon tables. The core of Armenian aesthetic thinking is St Nerses’s proposal that the world of experience should be divided into two classes of objects – the necessary and the pleasurable (the sensuous). According to St Nerses, the sensual pleasures depicted in the Canon Tables are not designed for the simple or uneducated folk but rather for the “perfected” ones, for the initiated.

As St Nerses writes, pleasures which primarily are not accounted as so important, are of great utility when they support the perfected ones, especially when they manifest colour, taste, smell, hearing and the rest of the human sences, in a way that help humans to ascend to the spiritual and to the rational enjoyment of the good tidings of God. “Which eye has not seen and which ear has not heard, and which is the heart of man that has not recalled, everything that God has prepared for his beloved ones.” Through the visual pleasures of the Canon Tables the human is supposed to ascend to the spiritual enjoyment of the Gospels themselves.

At the end of his Commentary, St Nerses calls the flowery meadows of the Canon Tables an “evangelical preparation” that precedes and prepares the spiritual path for the Gospel. He draws an analogy with the encampment of the Israelites at Sinai when they were required to wash and purify themselves before being admitted to the awesome vision of the Lord. Nerses calls the Canon Tables “bath of sight and hearing for those approaching the soaring peaks of God”. By washing his eyes in the beauty of these tables and by “circling with care in the tabernacle of this holy temple”, the reader was to prepare himself for the greater vision to be had in reading the text that followed.

By focusing attention on largely abstract decorations and colours, the Canon Tables were meant to focus the powers of his soul on the central mysteries of Christian revelation. This is an interesting role to ascribe to a work of art.

Two premises lie behind such an approach. The first is the frank acceptance of the sensuous as something good in itself and therefore worthy of the serious attention of the educated or the initiate. According to St Nerses, “God gave the lover of material things the understanding of the heavenly”. Accepting the premise, the artist found himself free to explore the limits of ornamentation and colour when illustrating his subject. [5] The second premise is that the most profound meanings contained in the Canon Tables must be left hidden. This is the exact opposite of the symbolic systems of western medieval art, which is didactic with each element labelled with specific meaning.

The Armenian Illuminated Canon Tables were designed for contemplation and their content had an openended significance. The illuminated Canon tables in Armenian Bible manuscripts dated from 5th to 14th century, are probably the best examples of this kind of art, where eccleciastical and folk elements are combined together allegorically in order to teach as well as to please the reader. In Armenian, the word used for the Canon Tables is “Khoran” (in Armenian: “Խորան”), a word that is also used to designate the Holy Altar on which every Sunday the “mystery profound” (the Incarnation to Ascension) is celebrated. Nerses Shnorhali expounds this idea further: “The mystery is not apparent to all, but only to a few, and its entirety is known to God”. Following on this, each of the ten Canon Tables is interpreted as a dwelling for one of the great mysteries of salvation history, as follows:

~

1. Τhe Blessed Trinity;

….. The First Priesthood of Angels: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones

..2. The Middle Priesthood of Angels: Dominions, Virtues, Powers

..3. The Third Priesthood of Angels: Principalities, Archangels, Angels

..4. The Garden of Paradise

..5. The Ark of Noah

..6. The Altar of Abraham

..7. The Holy of Holies

..8. The Tabernacle

..9. The Solomon’s Temple

10. The Holy Catholic Apostolic Church

~

Ten is the most important number for this set, and St Nerses calls it as ‘”a holy number and a gift of God”. According to Nerses, the number ten was chosen by Eusebius by divine inspiration. Ten is the number of the commandments, ten are the curtains of the temple, the parts of the body and its senses, the categories of Aristotle, the petitions of the Lord’s Prayer, the articles of the Nicene Creed, and the ages of the world. It is therefore a number of completeness. [6]

In almost all commentaries, Canon Table presentations use four colours: red, green, black and blue. Sometimes additional colours are mentioned: purple, calico, flax and sky blue, which in essence may be considered hues. According to the 8th century commentary attributed to Stepanos Syunetsi:

The first Canon Table is coloured in four hues that signify the symbol of the four elements of the first temple.

The second Canon Table is also coloured in four hues, where black represents the colour of “true existence”, as a divine symbol; red on black in the form of an arch symbolizes the blood of victims to save the apostates. If the inner part is black, and above it is red, in between comes blue, which symbolizes the spiritual in corporal life. The middle arch in gold is considered ecclesiastical; supposedly, the winged arch upon it shows King Melchisedek of the Old Testament, who represents Jesus Christ. While, the uppermost black arch is the symbol of Advent.

The third and fourth Canon Tables are also represented in four hues. The names of the principal colours — white, green and red — are the designations given to Sundays following Easter: i.e. New Sunday (white), Sunday of the World Church (Green Sunday) and Red Sunday, on which occasions the celebrant of the Divine Liturgy adorns matching colour vestments. [7]

Four kinds of flora are mentioned by St Nerses, which were probably represented in pairs in the outer margins. The date palm in the tables of the angels he took to refer to the lofty nature and sweet blessings of these heavenly creatures, but when he found them in the ninth table they referred to Christ, sprung from the root of David as truth sprang from the earth.

The olive tree has three associations for St Nerses: its greenness suggests the longevity of the patriarchs, the sourness of its fruit, the austerity of their lives, and its oil the illumination of their teaching. The lily also has many meanings: its colours of white, yellow and red mean purity, patience and manliness; the water lily signifies the patriarchs’ ability to rise above the world around them; the desert lily stands for the ascetics of the desert. Finally, the pomegranate refers to the sweetness of the New Law within the bitter rind of the Old Testament.

St Nerses offers an interpretation for six different species of birds in the Canon Tables. Birds played an important role in Armenian art from early on. The forty birds surrounding an eagle in the sixth-century Armenian mosaic in Jerusalem have been convincingly interpreted by many theologians as symbolic of the deceased flocking around Christ: Precedents for this positive use of bird symbolism can be derived from Sasanian and Syrian sources. [8]

In the Memorial Office, the image often emphasized for the souls of the departed is: “With new feathers were they adorned at thy resurrection, O holy Only-begotten”, or in the hymn: “Heavenly Jerusalem is the dwelling of the angels”, as well as within the verse: “Enoch and Elijah live in old age like doves”. [9]

As per the writings of St Nerses, the cock appearing in the ninth table: “close to the morning of righteousness, proclaimed the apparition of the ineffable light”. It is a symbol that stands for the advent of Christ. According to Stepanos Syunetsi, the gold feathers of the cock represent those who are purified and worthy of the Holy Spirit. It is “splendid and bold, commanding and awesome”. The cock in the margins of the New Testament represents St Peter the Apostle at the moment when he denied his Lord. Doves may stand for the gifts of the Holy Spirit, or for those who have received the gifts of the Holy Spirit, a symbolism developed in early Christian Armenia by St Agathangeghos (Agathangelos).

Both commentators associate the partridges with the “harlots” who by ruse came to have a role in Christ’s lineage. St Nerses explains that: ”’it is the way of partridges to steal eggs and make them its own, even as they (i.e. the three women) stole by cunning from the house of Abraham and his son the fruit of blessings, and became the fore-mothers of Christ”.

The tradition that made herons symbols of the apostles involved a peculiarity of the Armenian version of the Scriptures, alluding to Christ’s call to the apostles. As St Nerses writes, the apostles were fishermen, but Jesus made them “hunters of men”. Hence, the fishing birds have long been considered as an appropriate symbol of the apostles.

Finally, according to St Nerses, peacocks with their gold feathers represent the purity of angelic spirits. Whereas, for Stepanos Syunetsi they represent the vain attention to externals of the Jews of the Old Testament.

The introduction of monkeys and rampant lions in the Armenian manuscripts, caused mainly due to western influence. Those monkeys holding lighted candles symbolize the Church. Whereas, monkeys holding extinguished candles symbolize the Temple of Solomon, now extinguished. The Church has replaced the Temple as the dwelling place of the Divinity: “this is a dwelling of holiness and place of praise”.

The consistency among Armenian artists in their use of colours, ornaments and decorations as it is observed in diffrent locations, and in different chronological periods, can be mainly explained by the existence of a well founded literary tradition that survived through the ages. [10]

~

~

Armenian Illuminated Canon Tables, Canon I, by Malnazar, 1637, Matenadaran collection

~

~

Saint Nerses and the worship of icons

~

Nerses IV Klayetsi -Shnorhali (c. 1102-73), explaining the position of the Armenian Church in regard to image worship, he stated: “We accept them; we bow down before the image of our Saviour; we respect the images of all the saints, each one according to his ranks; we represent them in our churches and on our sacred vestments. But the same honour is not due to the representations of Christ, or of the cross, or to those of the saints. We honour and glorify the images of the saints, who are our intermediaries and our intercessors before God; but proskynesis (veneration) is offered to God, through them; for it is only due to the creator and not to the created …

The holy icons, the images and the names of the faithful servants of God, who by their nature are our fellow-servants, must be honoured and respected, each one according to his merits. In seeing their virtuous deeds represented on the pictures, we must take them as our models, and recall their sufferings in the cause of truth. Whoever insults them, does not insult the material out of which the picture is made, but him in whose name it is painted, be he the Lord or his servant”. [11]

As stated St Nerses Shnorhali: “Man was made in the image of God with regard to the soul and not his body”. This is a deliberate rejection of the sensual likeness of the image to the prototype, as the genuine means of truely understanding the model. [12]

St Nerses also speaks about the respect we due to the Holy Cross. He explains the reason why a cross must be anointed: “The Cross is the chariot and the throne on which Christ the King is ever present; proskynesis and adoration are therefore rendered to the crucified Christ, and not to the material throne. God is invisible by his nature; in bowing down before the visible cross, we do so before the invisible God, according to the commandments we received from the holy apostles. While with our bodily eyes we see its material and true shape, with the eyes of the spirit, and our faith, we perceive the invisible power of God united with it”. ]13] However, only the anointed crosses must be honoured, for divine power is then indivisibly united with them. Otherwise, the honour would be addressed to the mere matter, and the worship of what is created has been condemned by the holy books as idolatry”. [14]

~

~

Armenian Illuminated Canon Tables, Canon I, Mugni Gospels, 1060

~

~

Notes

[1] Nersessian Vrej, Treasures From The Ark 1700 Years of Armenian Christian Art’, The Paul J. Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2001, pp. 79-88

[2] Russell, James R., ‘Two interpretations of the Ten Canon Tables’ in Armenian Gospel Iconography: The Tradition of the Gladzor Gospel. Washington, DC, 1991, pp. 206-11.

[3] Hakobyan, G., Nerses Shnorhali. Erevan,1964.

[4] Nersessian, Vrej, ‘Das Beispiel eines Heiligen: Leben und Werk des Hi. Nerses Clajensis mit dem Beinamen Schnorhali’, in Die Kirche Armeniens, F. Heyer ed. Stuttgart, 1978, pp. 59-64; ‘The significance of the Bible for Saint Nerses Shnorhali’s Theology’, in Actes du Colloque ‘Les Lusignans et L’outre Mer’, C. Mutafian ed. Poitiers, 1993, pp. 218-27.

[5] Ghazaryan, V., ‘The doctrine of colour in Commentaries on Canon Tables’, Atti V Simposio, pp. 687-94; Khachatryan, Tigran, ‘Hogevor patkerembrnoghut’yiwne ev kanoni nshanakut’iwne ekeghetsakan kerparvestum’, Gandzasarlll (1993), 320-27.

[6] Thomson, R.W., ‘Number symbolism and patristic exegesis in some early Armenian writers’, Handes Amsoreay 1-12 (1976), pp. 131-2.

[7] Galoustian, Shnorhk’, Gunagegh Kirakiner ev Hogegalust. Istanbul, 1972; Barsamian, Khajag, Abp, The Calendar of the Armenian Church. New York, 1995, pp. 35-42.

[8] Evans, Helen, ‘Nonclassical sources for the Armenian mosaic near the Damascus gate in Jerusalem’, East of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the Formative period. DOP, 1980, pp. 217-22.

[9] Nersoyan, Divine Liturgy, pp. 120-21.

[10] Alishan, Ghewond, ‘Patkerusoyts Girk’, Gandzasarlll (1993), 329-52; IV (1994, 335-48.

[11] Nerses IV Klayetsi, Tught Endhanrakan, Jerusalem, 1871, pp. 98, 140-141.

[12] Nor Bargirk Haykazean Lezui, vol. II. Venice, 1837, Page 612.

[13] Nerses IV Klayetsi, Tught Endhanrakan, Jerusalem, 1871, page 272.

[14] Nerses IV Klayetsi, Tught Endhanrakan, Jerusalem, 1871, page 273.

~