~

“Khoran” The Illuminated Canon Tables

~

The Eusebian Canon Tables – Ammonius Sections

and their significance for the Church

~

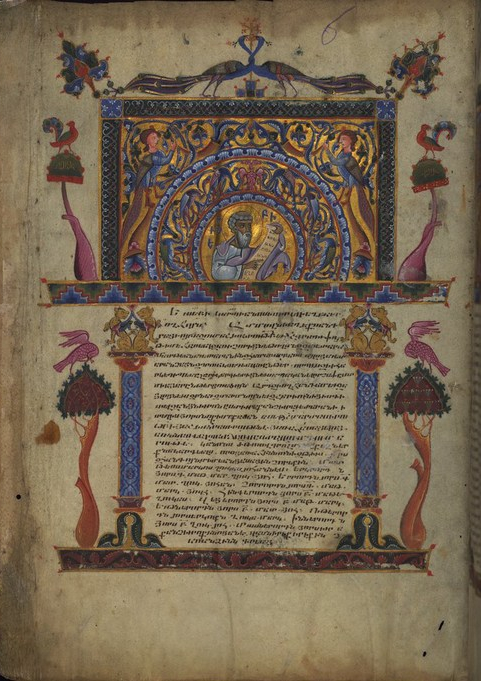

Armenian Illuminated Canon Tables, Preface “Letter to Carpianus”, Toros Roslin, Zeytun Gospels, 1256, Getty museum collection

~

~

~

Canon I “/” Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

Canon I “/” Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

~

Canon II “/” Matthew, Mark, Luke

Canon II “/” Matthew, Mark, Luke

~

Canon III “/” Matthew, Luke, John

Canon III “/” Matthew, Luke, John

~

Canon IV “/” Matthew, Mark, John

Canon IV “/” Matthew, Mark, John

~

Canon V “/” Matthew, Luke

Canon V “/” Matthew, Luke

~

Canon VI “/” Matthew, Mark

Canon VI “/” Matthew, Mark

~

Canon VII “/”Matthew, John

Canon VII “/”Matthew, John

~

Canon VIII“/”Luke, Mark

Canon VIII“/”Luke, Mark

~

Canon IX “/” Luke, John

Canon IX “/” Luke, John

~

Canon X “/” in Matthew only

Canon X “/” in Matthew only

~

Canon X “/” in Mark only

Canon X “/” in Mark only

~

Canon X “/” in Luke only

Canon X “/” in Luke only

~

Canon X “/” in John only

Canon X “/” in John only

~

Eusebius Letter to Carpianus

Eusebius Letter to Carpianus

~

~

~

~

The Gospel Harmony

~

A gospel harmony is an attempt to compile the canonical gospels of the New Testament into a single account. This may take the form either of a single, merged narrative, or a tabular format with one column for each gospel, technically known as a synopsis, even though the word harmony is often used for both. The terms harmony and synopsis have been used to refer to several different approaches for the consolidation of the canonical gospels.

The challenge in any form of harmonizing comprises that in different evangelical sources, the biblical events are sometimes described in a different order. The Synoptic Gospels, for instance, describe that Jesus was overturning tables in the Temple at Jerusalem in the last week of his life, whereas the Gospel of John records a counterpart event that is presented towards the beginning of His ministry. Researchers must either decide which might be the most probable sequence of the events, or conclude that separate events are hereby described. Anyway, researchers have long noted that the individual gospels are not written in a rigorously chronological format.

In many cases, the gospels diverge in their substantive description of an event. As an example, let us consider the incident involving the centurion whose servant was healed by Jesus. In the Gospel of Matthew the centurion comes to Jesus in person; whereas in the Gospel of Luke, the centurion sends Jewish elders. As long as these accounts are clearly describing the same event, the researcher must conclude which description shall be considered as the most accurate.

Based on the broadly accepted principle that the Gospels of Matthew and Luke were written by using the Gospel of Mark as a source, researchers seek to explain the differences between the texts in terms of this process of composition. For example, Mark refers to John the Baptist preaching the forgiveness of sins. A detail which is dropped by Matthew, perhaps in the belief that the forgiveness of sins was exclusively related to the ministry of Jesus. However, it is generally accepted that the divergences in the gospels are a relatively small part of the whole, and that the narrative in the gospels tends to show a great deal of overall similarity.

The “Diatessaron”, an influential work of Tatian, which dates to about AD 160, was perhaps the very first attempt to publish a so-called harmony of the gospels. Diatessaron is a harmony in the form of a single merged narrative. Variations based on the Diatessaron continued to appear in the Middle Ages, e.g. Codex Sangallensis (based on the 6th century Codex Fuldensis) dates to 830 and has a Latin column based on the Vulgate and an Old High German column that often resembles the Diatessaron, although errors frequently appear within it. The Liege harmony in the Limburg dialect (Liege University library item 437) is a key Western source of the Diatessaron and dates to 1280, although published much later. Two extant recensions of the Diatessaron were found in Medieval Italia. These are the so-called “Venetian” manuscript dated from the late 13th or early 14th century, and the “Tuscany” manuscript dated from the 14–15th century.

In the 3rd century, a Christian philosopher, Ammonius of Alexandria, developed the forerunner of the synopsis of the Gospels, a “harmony” based probably on the Diatessaron of Tatian. Nowadays, there are no extant copies of the Harmony of Ammonius. It is known only from a single reference in the letter of Eusebius of Caesaria to Carpianus. In this letter, Eusebius discusses his own approach, which has become universally known as the “Eusebian Canons”.

~

~

Armenian Illuminated Canon Tables, Preface “Letter to Carpianus”, Toros Roslin, 13th century, Matenadaran collection

~

~

Eusebian Canon Tables

~

Eusebian Canons (also known as “Eusebian sections” or sometimes as the “Eusebian Apparatus”) is a system of dividing the Gospels into sections according to their relevance. Because of its connection with an earlier work of Ammonius of Alexadria, Eusebian Canons are also called “Ammonian sections”. Eusebian Canons were widely used from the late Antiquity until the Middle Ages. The division of the Bible into chapters and verses as it is currently used in modern texts, is dated from the 13th century and onwards. Specifically, the division of the Bible into chapters is dated as early as from the 13th century, whereas the division of Bible into verses is dated as early as from 16th century.

Eusebius of Caesaria (265-340) was a historian of Christianity, a philosopher and theologian. He became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima (in Palestine) about 314 to 339 AD. He was a scholar of the Biblical canon. In general, he is regarded as an extremely educated Christian of his time.

Eusebius, in his survey on the material of the four Evangelists, divided the Gospels into sections based on the similarity of their content. Eusebius avoided to create a harmony in the form of a single merged narrative, by following the example of Tatian in “Diatessaron”. He considered that such a merger would have the inevitable result of ruining the sequential order of the gospels, as far as a continuous reading of the text was concerned. Keeping, however, both the body and sequence of the other gospels completely intact, he presented those sections into synoptical tables, so that to facilitate the search of pericopes (evangelical sections) with similar content from the Gospels. These tables were designated to serve as a synoptic concordance to the Four Gospels. They become later widely known as the “Eusebian Canon Tables”.

Eusebian Canon tables present the text of the four gospels arranged into parallel columns. Each column contains the text of each of the four gospels, being divided into sections. Those sections that contain similarities are placed on the same row, so as to facilitate the comparison among the Gospels. Because of the success of this concordance, Eusebius received a commission from the Byzantine emperor Constantine to execute fifty finely written and luxuriously bound copies of the Gospels containing the canons for the new churches of Constantinople. Unfortunately, none of these copies has been survived to date.

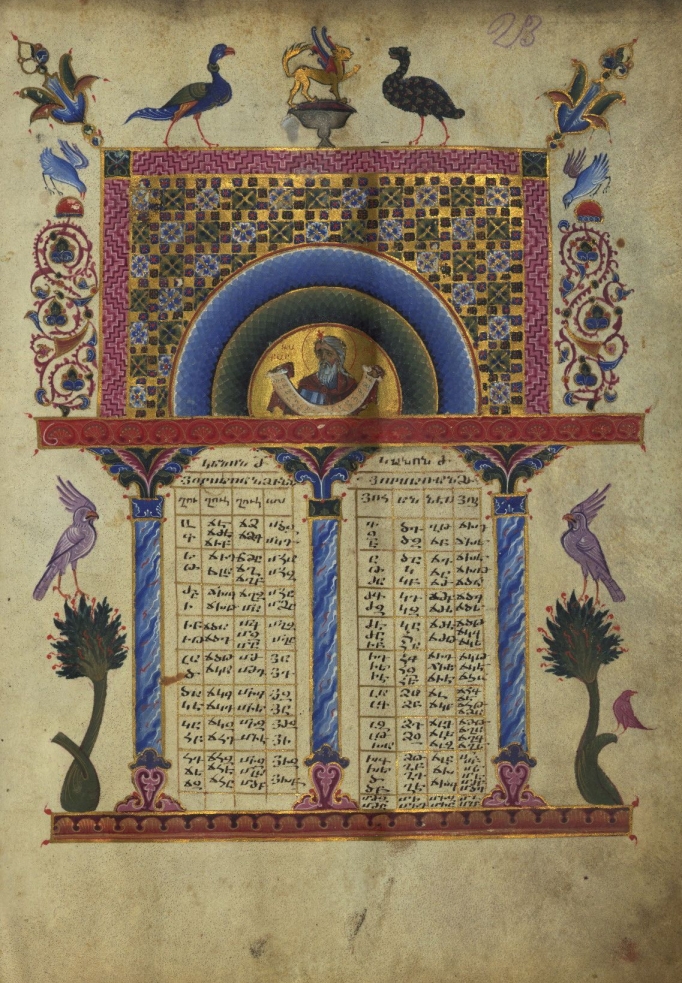

The Eusebius Canons gained a wide acceptance and popularity during the medieval times. They were always placed at the very beginning of the medieval manuscripts of the Gospels. Illuminated manuscript versions of the Eusebian Canon tables, which have been survived to date, have a great importance for the study of the art of medieval manuscripts. Canon tables are the most elaborately and lavishly decorated pages of the medieval manuscripts of the Gospels. The Eusebian Canon tables were actually included in almost all the Greek, Latin, Coptic and Armenian illuminated Bible manuscripts dated from the 5th century to the late Middle Ages.

The illuminated Canon tables in Armenian Bible manuscripts dated from 5th to 14th century, are probably the best examples of this kind of art, where eccleciastical and folk elements are combined together allegorically in order to teach as well as to please the reader. In Armenian, the word used for the Canon Tables is “Khoran” (in Armenian: “Խորան”), a word that is also used to designate the Holy Altar on which every Sunday the “mystery profound” is celebrated.

~

~

Eusebian Canons and Ammonius Sections

~

The division of the Gospels into sections, even though was analytically presented by Eusebius, actually dates back to Ammonius of Alexandria. Ammonius divided the Gospels into 1165 sections in total: 355 for Matthew, 235 for Mark, 343 for Luke, and 232 for John. This numbering is applicable in the most cases of manuscripts, even though it cannot be considered as a general rule.

Through the centuries, it has been a common belief that these divisions were devised by Ammonius of Alexandria at the beginning of the third century (c. 220), in connection with a “Harmony” of the Gospels, now lost, which he composed. It has been commonly believed that Ammonius was the first who divided the four Gospels into small numbered sections, which were similar in content and where the narratives were parallel in meaning. The Ammonian sections, organized and presented in tabular form, consisting of in total ten tables, used to be placed at the very beginning of the medieval manuscripts of the Gospels. These sections have been included in the margins of nearly all Greek, Latin, Coptic and Armenian manuscripts of the Bible, from the 5th century until the late Middle Ages.

Of late, however, the view that has been obtained among scholars is that the work of Ammonius was restricted to what Eusebius of Caesaria (265-340) states concerning it in his letter to Carpianus. Namely, Eusebius placed the parallel passages of the last three Gospels alongside with the text of St. Matthew. The sections hitherto credited to Ammonius, were ascribed to Eusebius. The Harmony of Ammonius suggested to Eusebius, as he himself describes us, is the idea of drawing up ten tables (canons) in which the sections were classified in such a way so as to make clear to the reader, at a glance, in which section each Gospel is in accordance with the others.

~

~

The Eusebius Letter to Carpianus

~

Eusebius’s explanatory letter to Carpianus has very often been reproduced and presented before the Canon tables. The “Letter to Carpianus” or “Letter of Eusebius” (in Latin: “Epistula ad Carpianum”) is the title traditionally given to a letter from Eusebius of Caesarea to a Christian named Carpianus. Even though we very little konw about Carpianus, the fact that Eusebius addresses to him, implies that he was an important person of the Church and the Christian Community.

In this letter, Eusebius explains his ingenious system of Gospel harmony, the Eusebian Canons (tables), ten in number, that divide the four Canonical gospels, and describes their purpose. Eusebius explains that Ammonius the Alexandrian created a system in which he placed sections of the gospels of Mark, Luke and John next to sections in Matthew that have a parallel meaning. As this disrupted the normal text order of the gospels of Mark, Luke and John, Eusebius used a system in which he placed the references to the parallel texts in ten tables or “Canons”.

The “Letter to Carpianus” has been included in almost all medieval Bible manuscripts, always placed at the very beginning, before Canon Tables. Illuminated manuscript versions of the Eusebian Canon tables, which have been survived to date, have inluded the full text of “Epistula ad Carpianum” in a separate page, placed before the Canon tables, always lavishly ornated and decorated. In most of the times, the image of an old man, apparently Eusebius himself, appears in a prominent position, in the top of the manuscript.

For further reading and understanding, at the end of this page there is an analytical presentation of Epistula ad Carpianum, including the original letter in Greek, along with a contemporary translation in english. Please see here

~

~

Canon Tables: structure and content

~

In the first nine tables, the numbers of the sections that are common to the four, or three, or two evangelists were placed in parallel columns. In the tenth table there were noted successively the sections special to each evangelist. Namely:

~

Canon 1: Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

Canon 2: Matthew, Mark, Luke

Canon 3: Matthew, Luke, John

Canon 4: Matthew, Mark, John

Canon 5: Matthew, Luke

Canon 6: Matthew, Mark

Canon 7: Matthew, John

Canon 8: Luke, Mark

Canon 9: Luke, John

Canon 10: Matthew only, Mark only, Luke only, John only

~

In the first nine tables, each column contained numbers of sections common to the four, or three, or two, evangelists. Each row contained those numbers of sections that are in common (to the four, or three, or two, evangelists). In the tenth table there are sections special to each evangelist.

~

~

~

~

However, it is interesting to notice that no canon table exists for sections common to: Mark, Luke & John (excluding Matthew). Also, no canon exists for the sections common to: Mark & John (excluding Matthew & Luke). This may be somehow explained due to the fact that Ammonius based his “harmony” by considering the gospel of St. Matthew as the basis of comparison with the other three Gospels. However, this cannot explain the fact that although the gospel of Matthew is used as the basis for the first 7 canons, this is not the case when it comes to Canon 8 (Luke & Mark) and Canon 9 (Luke & John).

The usefulness of these tables for the purpose of reference and comparison soon brought them into common use. From the 5th century until the late Middle Ages, the Ammonian sections, with references to the Eusebian tables, were indicated in the margin of nearly all the manuscripts of the Bible. As mentioned above, chapters and verses, as they are currently used, were not then in existence. The division in chapters dates from the 13th century, and the division into verses dates from the 16th century.

Ammonian sections do not all the times match exactly with the content of the “modern” division of biblical chapters and verses. In some cases, an Ammonian section may contain a part only from a biblical verse, or in many cases an Ammonian section may contain the second part (or the third part) from a biblical verse as well as the first part from the very next one.

By using these tables, the parallel texts could easily be looked up. But, yet it still remained possible to read a gospel in its normal order. The number of each “Ammonian section” was written in the margin of the manuscript, and underneath this numbering, another number indicator was written in coloured ink. The coloured number indicators referred to one of the ten Eusebian canons, in which the reference numbers were to be found out of the parallel sections of the Gospels, so as to easily identify any existing parallelisms. A reference to the tenth table would of course be shown, indicating that this section was proper to that evangelist alone.

As a result, the reader opens one of the four gospels at some point, wishing to go to a certain chapter in order to know what gospels recount similar things, and to find in each gospel the related passages in which the evangelists were led to speak about the same things. By using the reference number assigned for the section in which he is interested and looking for it within the table indicated by the red numeral below it, the reader will immediately discover from the titles at the head of the table how many and which gospels recount similar things. By going to the other gospels’ reference numbers that are in the same row as the reference number in the table he is looking at, and by looking them up in the related passages of each gospel, the reader will find similar things mentioned.

~

~

Examples

~

As example, for better understanding; if we wish to read about the institution of the Lord’s Supper, as it is mentioned in all four Gospels, Eusebian Canon Tables, and specifically Canons I & II, will provide us with the following information: (All sections below bear their Ammonian numbering shown in brackets, as well as the numbering in chapters and verses as commonly in use today)

~

~

Canon I

(in all four gospels)

~

[Mathew 284]: Mt 26.26

26 While they were eating, Jesus took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to the disciples, and said, “Take, eat; this is my body.”

[Mark 165]: Mk 14.22

22 While they were eating, he took a loaf of bread, and after blessing it he broke it, gave it to them, and said, “Take; this is my body.”

[Luke 266]: Lk 22.19

19 Then he took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.”

[John 55]: Jn 6.35A

35 Jesus said to them, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never be hungry.”

[John 63]: Jn 6.48

48 I am the bread of life

[John 65]: Jn 6.51

51 I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.”

[John 67]: Jn 6.55

55 For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink.”

~

~

~

Canon II

(in Matthew, Mark and Luke)

~

[Matthew 285]: Mt 26.27-29

27 Then he took a cup, and after giving thanks he gave it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you; 28 for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. 29 I tell you, I will never again drink of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new with you in my Father’s kingdom.”

[Mark 166]: Mk 14.23-25

23 Then he took a cup, and after giving thanks he gave it to them, and all of them drank from it. 24 He said to them, “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many. 25 Truly I tell you, I will never again drink of the fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.”

[Luke 265]: Lk 22.16-18

16 for I tell you, I will not eat it until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God.” 17 Then he took a cup, and after giving thanks he said, “Take this and divide it among yourselves; 18 for I tell you that from now on I will not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes.”

[Luke 267]: Lk 22.20

20 And he did the same with the cup after supper, saying, “ This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood.”

~

~

On the tables, for further reading and better understanding, all the sections bear not only their original Ammonian numbering (shown in brackets), but also the respective numbering in chapters and verses (as it is commonly in use today). For example, as it can be seen in Canon I, the Ammonian section “Matthew 8,” matches with what we commonly understand as “Matthew chapter 3 verse 3” (Mt 3:3). The Ammonian section “Luke 10” matches with Luke 3:16B (with the second part of verse 16 only). The Ammonian section “Mark 27” matches with Mark 3:7B-11A (the second part of verse 7, together with verses 8,9,10 and the first part of verse 11). Please see here

~

~

Canon I “/” Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

Canon I “/” Matthew, Mark, Luke, John

Canon II “/” Matthew, Mark, Luke

Canon II “/” Matthew, Mark, Luke

Canon III “/” Matthew, Luke, John

Canon III “/” Matthew, Luke, John

Canon IV “/” Matthew, Mark, John

Canon IV “/” Matthew, Mark, John

Canon V “/” Matthew, Luke

Canon V “/” Matthew, Luke

Canon VI “/” Matthew, Mark

Canon VI “/” Matthew, Mark

Canon VII “/” Matthew, John

Canon VII “/” Matthew, John

Canon VIII “/” Luke, Mark

Canon VIII “/” Luke, Mark

Canon IX “/” Luke, John

Canon IX “/” Luke, John

Canon X “/” in Matthew only

Canon X “/” in Matthew only

Canon X “/” in Mark only

Canon X “/” in Mark only

Canon X “/” in Luke only

Canon X “/” in Luke only

Canon X “/” in John only

Canon X “/” in John only

Eusebius Letter to Carpianus

Eusebius Letter to Carpianus

~

~

~

Armenian Illuminated Canon Tables, Canon I, Toros Roslin, 13th century, Matenadaran collection

~

~